Pursue What You Prayed For

God by His Spirit so dwells in the elect that they do not become inactive, but are moved to act by Him; so that their will is not taken away, but is reformed and exercised by the influence of the Holy Spirit.

- John Calvin

He doth not so work our mortification in us as not to keep it still an act of our obedience. The Holy Ghost works in us and upon us, as we are fit to be wrought in and upon; that is, so as to preserve our own liberty and free obedience. He works upon our understandings, wills, consciences, and affections, agreeably to their own natures; he works in us and with us, not against us or without us; so that his assistance is an encouragement as to the facilitating of the work, and no occasion of neglect as to the work itself.

- John Owen

The significance of the request “Lord, teach us to pray,” only grows in mind as my family continues to learn to pray (Luke 11:1). Prayer may be the thing I thought least about when imagining all I would need to teach my children in order to raise them in the Lord. And yet, to prayer we return again, and again, and again. Prayer is more important to the spiritual formation of the children than I ever realized. It is also connected to everything else in our shared life.

When we read the Bible, we learn to pray. We all sat with our mouths open when Liam, who was four at the time, prayed “Our Father in heaven, thank you that you loved us before you made the world” (Arminius has his work cut out for him with Liam). When we learn the creeds, we learn to pray. I don’t think Christ's ascension would have entered into our praying if we were not memorising the creeds. When we learn theology, we learn to pray. It took the children a while to naturally address God directly in prayer, and not some unspecified deity, who I assume was supposed to report these prayers to the true God at his nearest convenience ("we pray that God would help us to…"). Now we have an eight year old who prompts the younger ones about this: “Didi, you’re speaking to God…” Prayer is also where the children have learnt to speak about God the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. And when we encounter nature - our own, and the way God’s world works - we learn to pray. We are always making adjustments and adaptations to our prayers as new data comes in each new day.

Our current project is learning to connect our prayer with our piety (by which I mean our mode of life in Christ). It is difficult to connect them at any age. So of course it is difficult when starting out. While the children are still cute it can be quite funny to listen to them pray confidently against impatience over breakfast and then leap headlong into impatience before anyone has even mentioned second breakfast (by the time elevenses has rolled around all has gone to the dogs, naturally). But the cuteness will… evolve. And the issue underneath, on some reflection, is important.

As I think about it I realise that this combination of confident praying and bold sinning (even in those things we have prayed against) may reveal some underdeveloped theology; possibly some poor theology. It may reveal that we (I’m lumping us in with the children now) believe prayer is magical on the one hand, or meaningless on the other. If it is meaningless it is not causally connected with anything that follows it, and we think no further about what we prayed for. No wonder we sin boldly. If it is magical it is very much causally connected with what follows, so much so that we need not think further about what we prayed for - Accio, patience!

The middle is missing. We need to know and believe that our praying and piety are supposed to be connected, actively, by us! If you have had your head in reformed sermons or books on these matters you will know that salvation (specifically regeneration and justification) is monergistic (one working), but sanctification (to narrow in a little from piety) is not. In sanctification we have work to do. It will be shoddy in many places. It will be half-hearted many times. But like the homework, the dishes, and the trash, it needs to be done (2 Thes 2:13).

And so our current catch phrase for our current project is: “pursue what you prayed for!” We are now praying very specifically in the morning for at least one contemporary temptation, and then reminding each other when the temptation comes, to (all together now) “pursue what you prayed for!” Interestingly, children enjoy being held accountable to things. They enjoy holding parents accountable slightly more. So join the fun.

But a little more on the meat of this idea. For many years (possibly many centuries) Professor Allan Chapple (in Perth, Australia) has been teaching seminary students “responsible dependence” in the Christian life. Responsible dependence is the straight and narrow path with two ditches on either side. On the one side is responsible independence. This is where we are very active in our piety, but depending entirely on ourselves. This is also called pride. On the other side is irresponsible dependence. This is where we “let go and let God.” Here we may pray frequently, but instead of leaning into the answers to those prayers, we sit back and watch for a miracle. This is the side of the ditch our family is addressing with, “Pursue what you prayed for!” And there are biblical examples of this way of thinking.

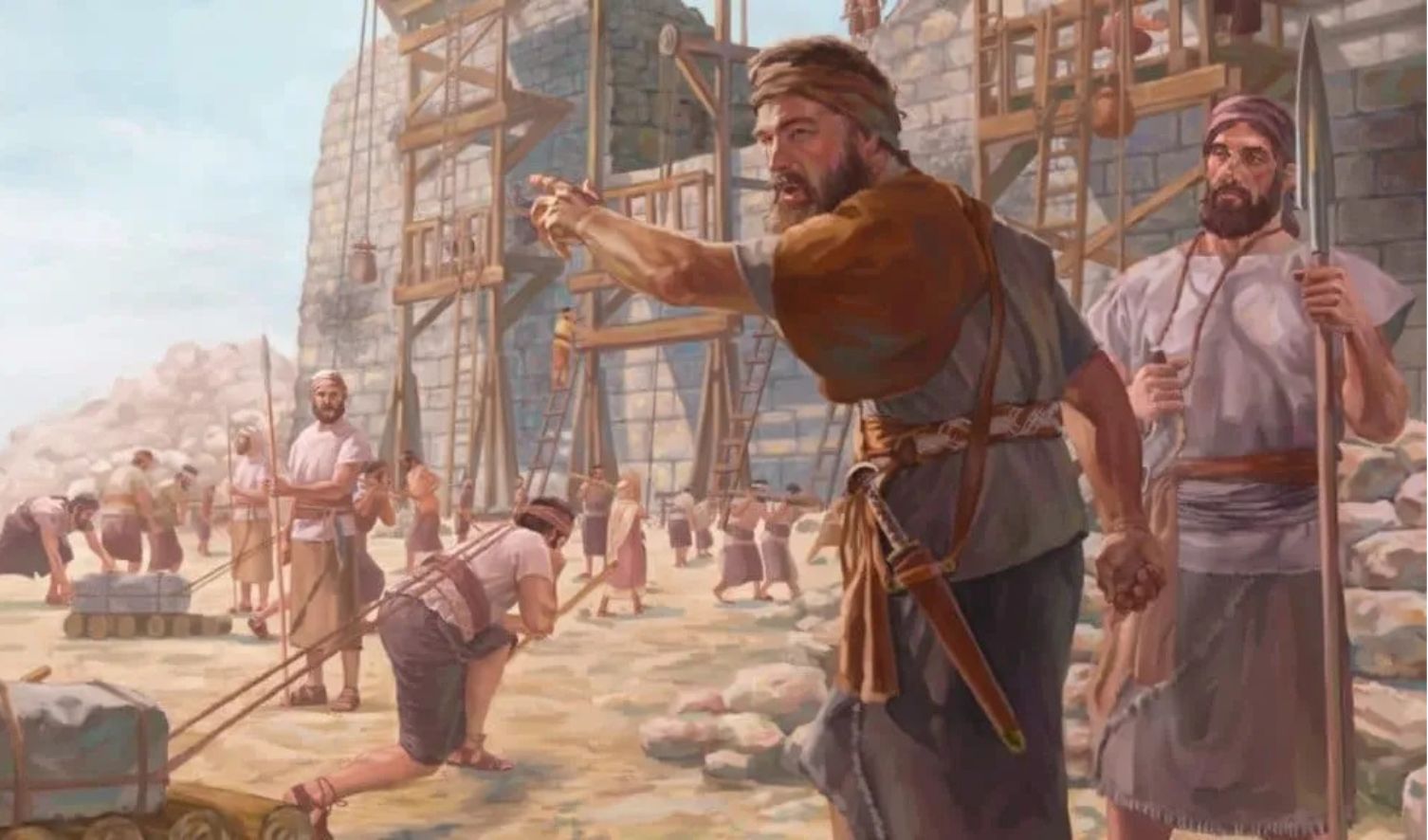

Nehemiah is especially good at this. The story begins with Nehemiah mourning over the plight of the survivors of the exile, whose beloved Jerusalem is broken down and burned with fire. When the king notices Nehemiah’s sad face and inquires about it, Nehemiah doesn’t retreat to the prayer closet and wait for a miracle (irresponsible dependence). Neither does he race ahead in his own strength and wisdom (responsible dependence).

2 Therefore the king said to me, “Why is your face sad, since you are not sick? This is nothing but sorrow of heart.” So I became dreadfully afraid, 3 and said to the king, “May the king live forever! Why should my face not be sad, when the city, the place of my fathers’ tombs, lies waste, and its gates are burned with fire?” 4 Then the king said to me, “What do you request?” So I prayed to the God of heaven (dependence). 5 And I said to the king, “If it pleases the king, and if your servant has found favor in your sight, I ask that you send me to Judah (responsible), to the city of my fathers’ tombs, that I may rebuild it.”

Later in the story when Sanbalat and company seek to disrupt the building of the wall Nehemiah holds the center again.

7 Now it happened, when Sanballat, Tobiah, the Arabs, the Ammonites, and the Ashdodites heard that the walls of Jerusalem were being restored and the gaps were beginning to be closed, that they became very angry, 8 and all of them conspired together to come and attack Jerusalem and create confusion. 9 Nevertheless we made our prayer to our God (dependence), and because of [Sanabalat and company] we set a watch against them day and night (responsible).

In both instances it would have been easy to fall into one of the two ditches. But in both instances Nehemiah prayed, and then pursued what he prayed for. His praying showed that he was dependent on his God. But his action showed that to him prayer was neither magical nor meaningless.

If someone needs further convincing of the doctrine I am setting forth I will resort to the words of Aquinas: “The authority of the Apostle suffices.”

12 Therefore, my beloved, as you have always obeyed, not as in my presence only, but now much more in my absence, work out your own salvation (responsible) with fear and trembling; 13 for it is God who works in you (dependence) both to will and to do for His good pleasure.

Notice that Paul does not commend our work only, or God’s work only, but both, and working together. Notice that he even logically relates both workers, such that God’s work provides the basis and impetus for our work (the “for” connecting the two workers does this).

All this is to make a simple point about prayer. Our praying is not supposed to be disconnected from our effort to live a godly life, or a substitute for our labour. In fact, our praying can function as a target, a direction for us to lean into. An invitation we send to ourselves to be part of the process, as it were. Who was it who said ‘prayer was really about conforming ourselves to God’s will, not conforming Him to ours’? Probably Lewis.

Practically, all of this alters my approach. I will not immediately rebuke the children for abandoning their prayers for patience, or gentleness, or generosity, or love, between first and second breakfast. Instead I will remind them of what they prayed for. I will invite them to make themselves available for God’s answers to those prayers. “Why don’t we pursue what we prayed for this morning, sweetheart? Let’s try it again, but gently.” “Son, didn’t you pray about this this morning? Let’s try it again, but with self-control.”

It also provides us an opportunity to pray again. It is easy to fall into the trap of praying all our prayers at the beginning and end of the day. But Nehemiah seems to have popped up to the throne of grace mid-conversation with Artaxerxes. I am writing this in the afternoon, and just this morning I had the children revisit their morning prayers again, and, 5 minutes after that, to pray again to confess their sins against each other in a spat we have all forgotten. But I have not forgotten that we prayed. And I don’t think they have either.

With this we also have a new little catechism (for more of these, drop by here).

Father: Well, we’ve prayed for it.

Children: God will do it.

All: Let’s pursue it!

And so, on we go, pursuing a piety that pleases the Lord. And by His grace we will get there, one prayer at a time.